Graffiti is dead. Or so we were told by a woman idling outside a Brooklyn art gallery. Yelled at, is more accurate. She was definitely yelling. “You’re wasting your time! It’s not real! They’re all sell outs!”

Our Free Tour By Foot of Bushwick had suddenly turned into a heated trial; the merciless prosecutor across the street passionately trying to convince us, the jury, that the defendant, our tour guide, was taking us for a ride. Real graffiti hasn’t existed since the 80s, she argued.

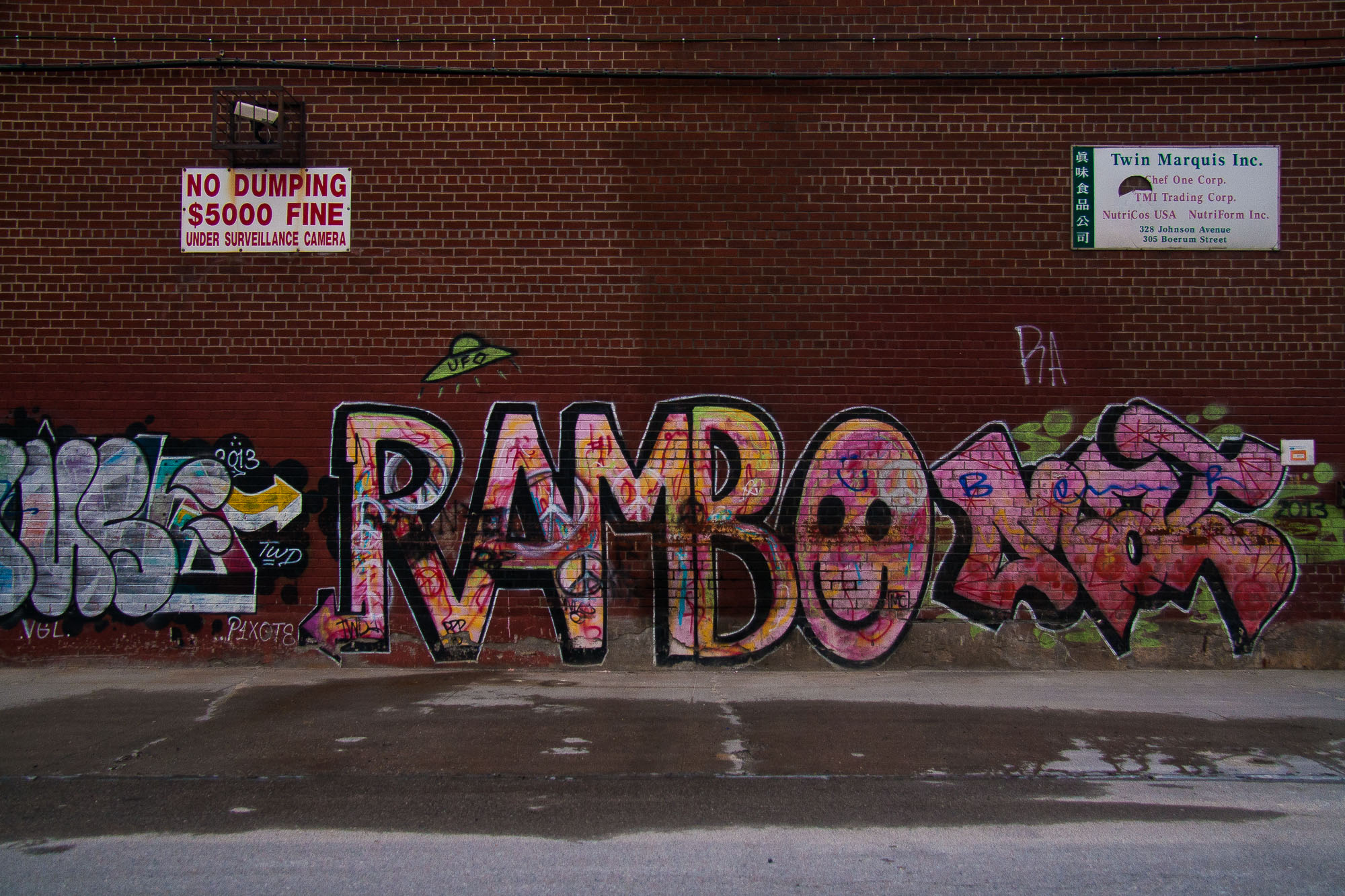

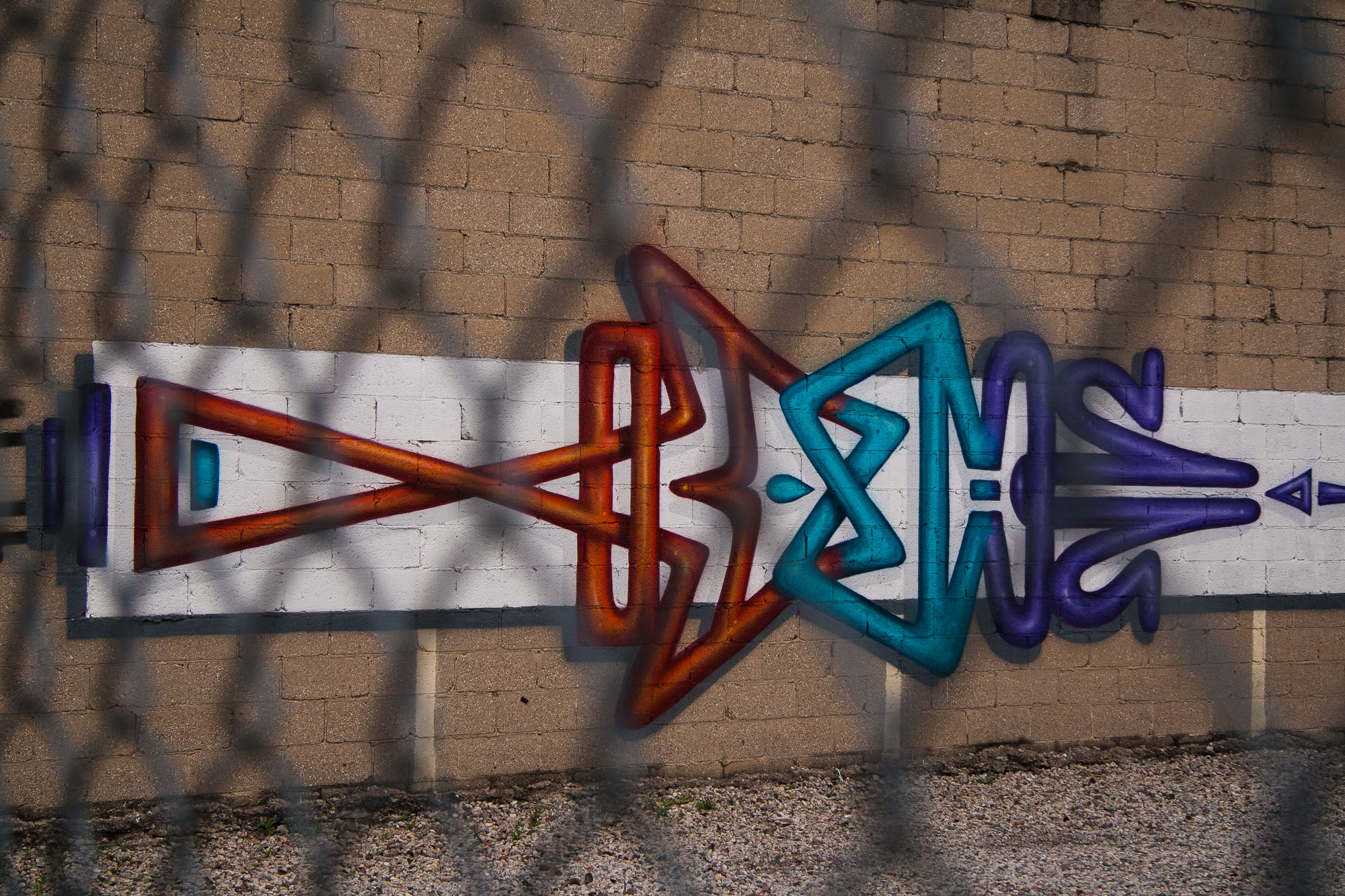

Our walk around the working class neighborhood on the north side of New York’s most populous borough suggested otherwise; graffiti, now more popularly referred to as street art, is very much alive and well.

My first experience of modern graffiti culture was at the start of high school. It wasn’t a typical South African school; we didn’t wear uniform, smoking was very much allowed and the cops were forever turning up to conduct raids. I had a very colourful bunch of peers – musicians, artists, hustlers and drug dealers. And, of course, graffiti writers.

When us youngins had gained the trust of our seniors, we were let in on who’s tag was whose, and I very much enjoyed riding around Johannesburg playing spot the bomb. I grew up with a sister who was constantly drawing or painting – anything that materialises from paint or ink is art to me.

Graffiti in South Africa runs much deeper than just a few artistic kids choosing walls as their canvas, of course; it played a major role in anti-apartheid demonstrations and walls and bridges continue to be an outlet for people to express their political views, much like the Berlin Wall.

But graffiti culture as we know it first emerged in New York City at the end of the 60s, specifically in Washington Heights and the Bronx. Writers tagged combinations of their names and street numbers, a convention made famous by Julio 204, Cay 161, Tracy 168, and Taki 183.

When the New York Times ran an article on Taki 183 in 1971, writers began to compete for who could be the most noticed. It was around that time that Taki, and another writer Tracy 168, began to tag subway trains so that their work would be taken throughout the city.

The subculture soon grew beyond the northern parts of Manhattan and into Brooklyn. Bubble lettering was replaced with the new “wildstyle” and writers began to add illustrations and characters to their tags. Up until this point, budget cuts had prevented the authorities from removing the graffiti in any successful way, but by the mid 70s, the city had declared war. Graffiti was upgraded from an annoying nuisance to a crime.

With the new classification came new security measures, posing new challenges for writers; increased police surveillance, razor wire and guard dogs forced them away from the trains and into the streets, where the crack epidemic was taking over. Restrictions were placed on paint sale, graffiti on trains was cleaned up and painted over, and legislation was underway to make penalties harsher for offenders. As a result, writers had to compete for space, offending property owners and becoming more territorial in the process, and started bombing in gangs.

In the 80s, graffiti and street art became linked with the emerging hip-hop scene. This helped to spread the culture internationally; Fab 5 Freddy was mentioned in and starred in the video for the 1981 hit Rapture by Blondie, and two iconic films about the movement, Style Wars and Wild Style, were released in 1983.

But the Transit Authority had also implemented a five-year plan to eradicate street art. In what became known as the “die-hard” era, graffiti culture took a step back. The last tagged train went out of service in 1989, and with the subway essentially inaccessible, writers had to find new ways to express themselves. Artists like Claw Money and Zephyr took to rooftops to display their art as the movement returned to the streets.

New York City declared the war on graffiti over, but by then the movement had already spread to the UK, where artists like Nick Walker, 3D, Inkie and Banksy were making ground.

In the 20 years that have followed, graffiti has become more and more accepted as an art form, with works starting to feature heavily in galleries and museums. Artists like King Robbo, Miss Van, Gaia, Blu, David Choe and Faith 47 are internationally renowned and often commissioned for special works, while the art of Banksy has inspired more than half the hipster population’s tattoos.

Many people still dismiss the art form as vandalism, however. Bombing is still illegal in New York City, as is the sale of spray paint, broad tipped markers or etching paint to anyone under the age of 18.

And in Bushwick, Joseph Ficalora, the local resident who curates the enormous outdoor gallery that stretches from Jefferson Street down to Saint Nicholas Avenue, has to constantly wrangle for permits to keep the art on the walls.

And in Bushwick, Joseph Ficalora, the local resident who curates the enormous outdoor gallery that stretches from Jefferson Street down to Saint Nicholas Avenue, has to constantly wrangle for permits to keep the art on the walls.

In some cases, dedication to the craft has even resulted in death.

But the push-back is real; artists are still tagging the subways, even though their work is wiped before the trains leave the yard. Their art is preserved on Instagram instead, under the hashtag #cleantrain.

In a recent episode of Showtime’s Homeland, the Egyptian artists tasked with decorating the set of a Syrian refugee camp with graffiti added their own secret protest message in Arabic: “Homeland is racist.”

On the streets of Mexico, graffiti artists are pushing the limits of free speech in the newly democratic country by using its walls to voice messages of social and political protest.

And most recently, a controversial collection of anti-nuclear text and symbols was found spray-painted on the corpses of sperm whales that washed ashore in the UK.

The message may not always be well-received, but it is clear: graffiti is not dead.

The tour lasts approximately 2 hours and starts outside the Fine and Raw chocolate shop (see map). It’s name-your-own-price, but reservations are required. Click here for more details.