In the final months of my last year at university, I took a trip to Hogsback, a small village in the Eastern Cape, to meet a potter named Anton. He agreed to be the subject of a soundslide I was producing for my portfolio and was kind enough to let me shadow him for a day. Tucked away in the forests of the Amatole Mountains, his studio overlooked a carpet of tree tops and was filled with the chirping of the forest’s louder residents.

There must be something about potters and the woods, I thought to myself as I watched the road disappear from the back of Conor’s car. He, Mark and I had spent the morning exploring Hita’s historic merchant district and were on our way to a nearby village in the Kyushu Mountains dedicated entirely to the pottery craft.

Much like Hogsback, Onta is surrounded be dense woodland and far removed from the bustle of the modern world. The soundtrack is different, though. Churns and splashes and thumps echo throughout the small settlement – the distinct song of the karausu that line the river and powder the clay.

The giant, see-saw hammers are integral to the production of ontayaki – a heavy-duty ceramic that the village is famous for. When the large hollow on one side fills with water, it sends the sharpened point on the other side whacking down into yellow clay.

The karausu are also a testament to the preservation of tradition; for 300 years, the knowledge and skills required to produce ontayaki have been passed down from father to son.

Ten families living in the village today still operate kilns, performing each of the steps in the pottery-making process manually. And to ensure that there will be plenty of resources for future generations, they have limited themselves to just two wheels per workshop.

Ontayaki was formed in the mid-Edo period by two Kyushu potters, Yanase Sanemon and Kuroki Jyuubi. They had been influenced by the climbing kiln that was brought to Japan from China.

The ceramic started to gain popularity when the philosopher and founder of the Mingei folk craft movement, Yanagi Soetsu, came across it for the first time in a pottery shop in Fukuoka. He was taken by the simple yet beautiful design and decided to travel to Onta to learn more about the craft.

In the 1950s, the world renowned potter Bernard Leach visited Onta to spend a short period studying ontayaki and this also helped to put the village on the map. Now, ceramics shops in Fukuoka and Tokyo are its biggest customers, ordering the handmade wares in bulk.

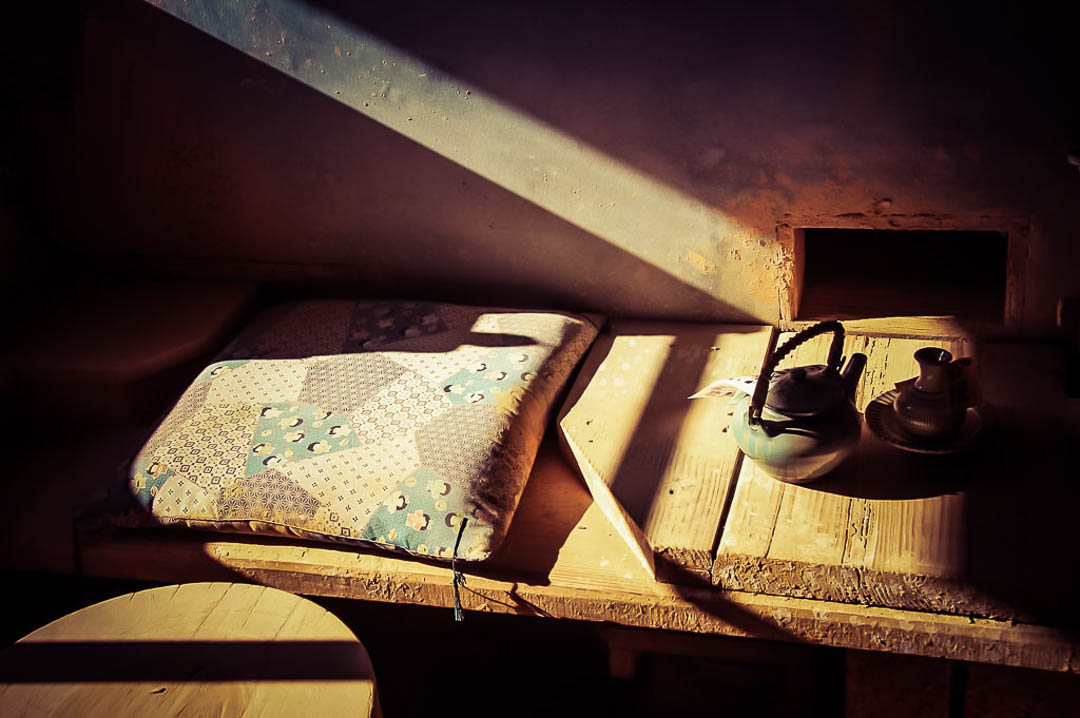

Despite its fame, Onta has remained as it was centuries ago. Every house has its own shop, but life revolves around the production process and does not stop for visitors; you are free to explore on your own while the locals go about their business and will often have to go looking for them if you want to make a purchase.

But a purchase you will want to make. Each piece is handmade and unique, and as reasonably priced as you will ever find it: the mark-up on wares sold in Fukuoka and Tokyo is considerable. I came away with a yellow-turquoise mug decorated with black comb patterns that look like the slash of a tiger’s paw.

Each family uses different colours and patterns in their designs, but all the pottery is marked with the same stamp to represent the collective effort of the village in the production process.

A tight-knit community almost completely removed from the world…it makes sense in a way. As Anton once explained all those years ago in Hogsback, “You need to enter into the fire with your imagination to figure out how the kiln works and how the fire is flowing past your pots. And in doing that, something happens to the potter… you become someone else.”